For professional singers working from home during the pandemic, singing online together has been nigh on impossible because of latency or time lag that puts them out of sync. Now a new technology promises to iron out these glitches.

When the San Francisco Opera started remote chorus rehearsals during lockdown “traditional video conference platforms didn’t work”, says Matthew Shilvock, the opera’s general director.

They kept chorus rehearsals going by Zoom, with a one-way feed, but latency – the time delay over remote connections – meant everyone other than the director had to stay on mute.

So the San Francisco Opera, like other companies, went through the rigmarole of making layered recordings, whereby the pianist would lay down a track, one singer would sing on top of that, another on top of that, and so on.

“You can make some beautiful music, but there’s no synchronicity or reactivity from one musician to another,” says Mr Shilvock.

Then he learned of a small Swedish tech start-up, Elk, and the Aloha software that they were beginning to beta test.

It was “kind of a game changer, with the very intriguing idea you could make music simultaneously and latency-free in remote locations,” he explains.

Every breath you take

There was a moment when one of the opera’s pianists was talking about this software which Mr Shilvock says he’ll never forget: “It’s allowed me to hear a singer breathe again,” said the pianist, an important element of the dynamic between an accompanist and performer.

As the San Francisco Opera moved into 2021, its young artists programme started using Aloha in earnest for sessions with a voice coach at the piano.

These are “so hard to do in Zoom, because there’s no immediacy of reaction”, Mr Shilvock says.

The Opera also used Aloha to prepare for a production of the Barber of Seville it is currently performing at the Marin County fairgrounds, in the northwest Bay Area, with drive-in audiences.

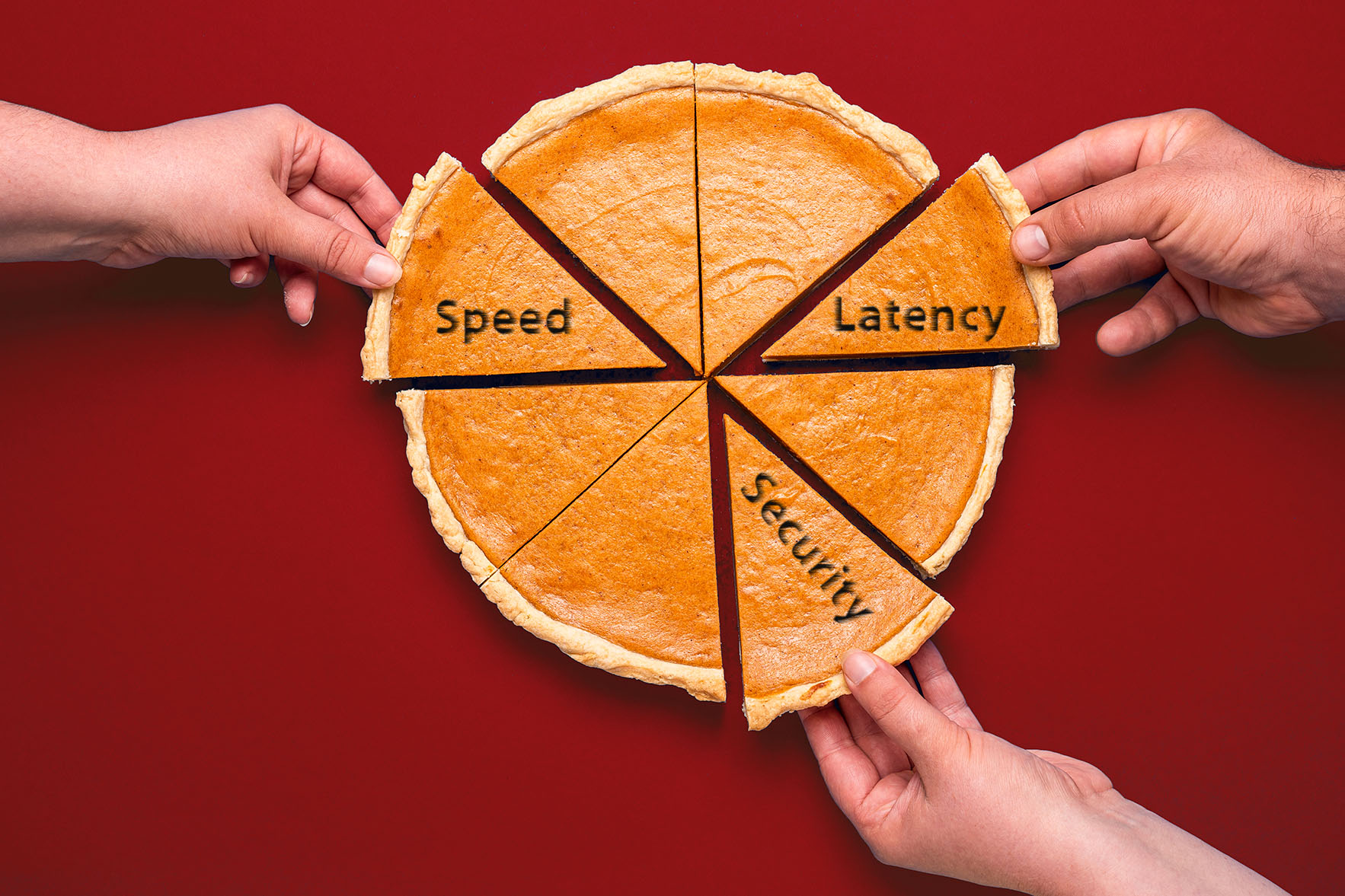

“Right now, we probably have 500 to 600 milliseconds [of latency] between us,” explains says Björn Ehlers, who works for Elk in Stockholm, and for 10 years ran Ramjac, a Swedish record label.

Such irregular and jittery latency, which is up to 0.6 seconds, can cause people trying to sing or play in unison to go out of sync very quickly.

With Aloha “we get down to 20 milliseconds”. For context, nine milliseconds is “basically you and me standing three metres apart in the same room”, says Mr Ehlers.

Aria code

There are basically three processes that can add latency when you send audio over the internet, he explains.

The first is taking audio, encoding it, and preparing it for transmission. The second is latency in the network itself. The third is at the receiving end, taking the encoded content and converting it back into audio.

Aloha’s combination of software running on a dedicated processor – both optimised specifically for audio – eliminates the first and third steps, making the process much faster.

Vodafone has been working with Elk’s founders to help them prepare to make use of 5G. Currently, Aloha makes use of fibre broadband connections. But with 5G, it will be able to connect musicians through the mobile network alone.

In the future, 5G can remove the need for the standalone processing hardware part of Aloha, which is currently based around a pocket-sized Raspberry Pi computer. Then “all this can be built into a digital keyboard, mixer, or you could basically have a 5G enabled microphone”, says Mr Ehlers.

Vodafone’s experts “have been very helpful in providing us with test feedback, especially on the 5G side that we see as the future for Aloha,” says Michele Benincaso, Elk’s Italian founder, who previously studied violin-making in Antonio Stradivari’s hometown of Cremona.

More recently, Elk started exploring opportunities in edge computing with Vodafone, which “looks like one of the more exciting and innovative areas of collaboration”, Mr Benincaso adds.

Low latency networks, combined with services like Aloha, make it “an exciting time despite the current difficulties” for music, says Santiago Tenorio, Vodafone’s Head of Group Network Architecture.

And “musicians, and even fans, will be able to collaborate instantaneously from different parts of the world”, he says.

Aloha is just the beginning

Just as Zoom enabled meetings to happen online, “Elk has opened up the door for that to happen musically as well, plus just a huge source of fun and engagement by just jamming with other musicians,” observes Mr Shilvock.

As an opera company in San Francisco, close to the home of the tech sector, “the energy and the drive to find solutions through technology is just so much part of the DNA of the city,” he explains.

Credits: Stefan Egerstrom

One lockdown project for the opera was a series of podcast miniatures, exploring “the relationship between a singer and singing, what is the meaning of singing to a singer, as it relates to their sense of community, family, and place,” Mr Shilvock says.

Bridges to singers’ personal traditions outside opera, such as Gospel, Samoan, and Bluegrass music, speak to the universality of song, he notes.

Developing productions more digitally means “you can make real-time course corrections”, understanding specifics of how audiences are watching pieces, and allowing music and audio-focused companies to “recalibrate on the fly”.

The classical music world might need all this.

“I believe the bar is going to be higher to inspire someone to attend an event in person”, observes the director.

Arts companies are beginning to think much more about how to “speak to a broader group of people and tell stories that matter to local communities.”

Technology could be the key to making music more accessible to a much wider, more diverse audience.

Stay up-to-date with the very latest news from Vodafone UK by following us on Twitter and signing up for News Centre website notifications.