The Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra's blockbuster camera has some obvious and not-so obvious tricks up its sleeve.

The Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra’s most eye-catching feature has to be its 200-megapixel (MP) main camera which, on paper and in pure numbers, surpasses almost all other phones and even many dedicated cameras.

Yet, by default, it shoots 12MP images. While head scratching at first glance, this is a deliberate choice that uses some clever behind-the-scenes engineering.

By shooting in 12MP by default, the S23 Ultra’s 200MP camera is using a technique called ‘pixel binning’. This is where the camera’s imaging sensor, a chip that turns light from the camera’s lens into the digital data that makes up your photos, groups together multiple physical pixels and treats them as single virtual pixels.

It does this because the copious number of pixels on that 200MP imaging sensor, while great at recording fine details, are so physically small that they’re limited in the amount of light they can collect.

Pixel binning helps overcome this as the single virtual pixels, by working together, can capture more light than the multiple physical pixels can individually. By pixel binning, the S23 Ultra’s main camera can produce 12MP photos with the best of both worlds – plenty of detail in all sorts of lighting conditions.

To illustrate the abilities of the S23 Ultra’s main camera, we pitted it against the Samsung Galaxy S20 in some photographically demanding scenarios. We also point out when you might want to use the option of shooting in full 200MP mode, rather than the default pixel-binned 12MP, and why.

Note: all images have been resized for faster webpage loading, but are otherwise unedited. Each image can be viewed in a larger size by right-clicking/long-pressing it and opening it in a new browser tab or window.

Faces in low light

In this dimly-2lit scene with only a flickering streetlamp for lighting, the S23 Ultra’s pixel-binned 12MP image is noticeably sharper and packed with more detail than the S20’s effort. So much so that it’s possible to make out the strands and patterns of fur on the face of this friendly little cat – including the fact that his nose is balding a little. The S23 Ultra has also avoided the S20’s common misstep of over-brightening the right side of the cat’s face where the street lighting shines through the edges of his fur.

Scenery in low light

The S23 Ultra’s pixel-binning showed off its chops once again in this shot of spring blossoms at night, backlit by a stark streetlamp. It fared far better at reproducing the folds and creases of each petal, even compensating for motion blur caused by the wind blowing the blossoms about back and forth.

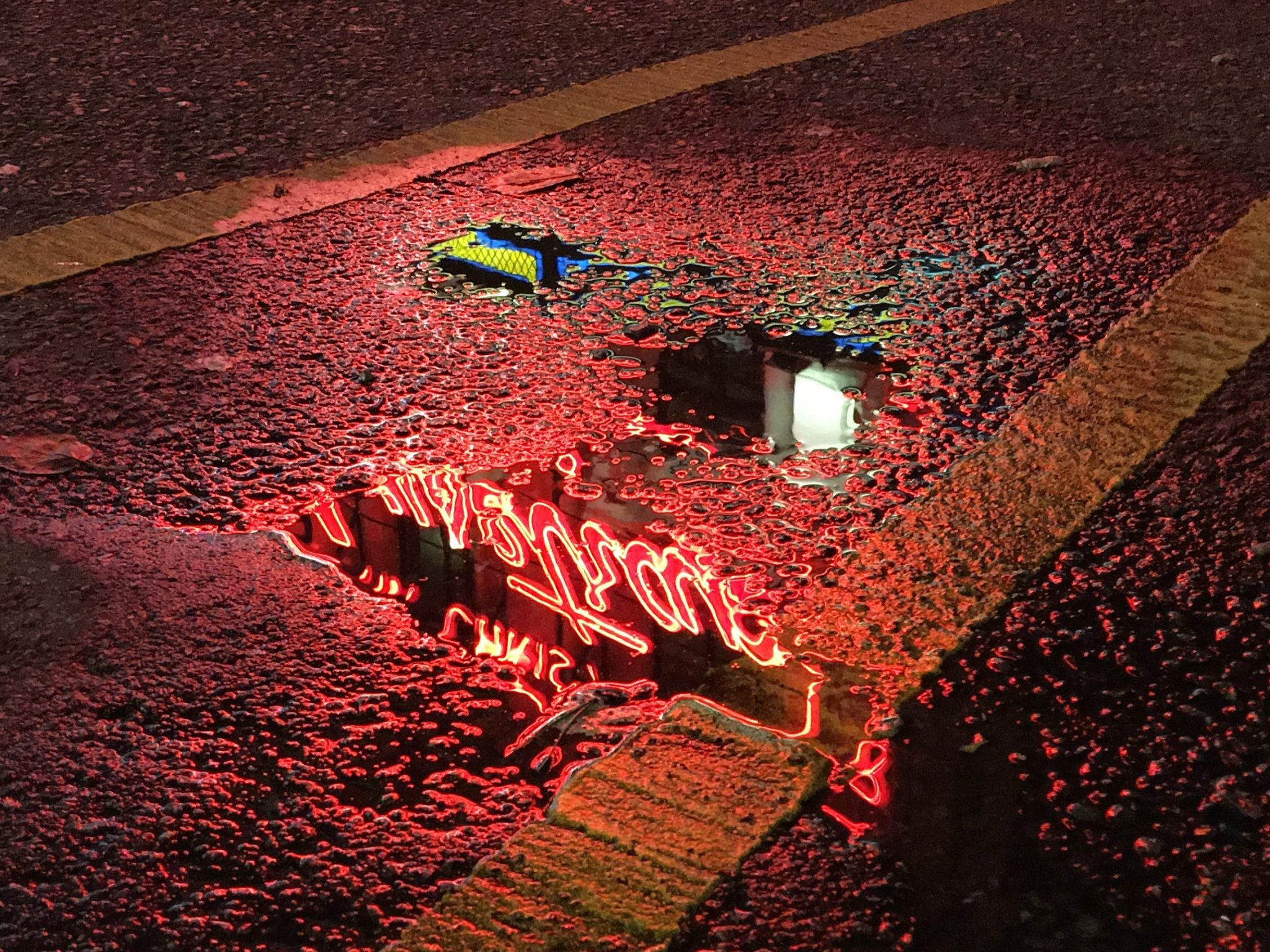

Zooming in

One scenario where you may want to turn-off pixel-binning and shoot in full 200MP is when you want to ‘zoom’ in on a faraway detail, such as this pair of graffiti-decorated columns at London’s Southbank Skatepark, by cropping in.

While it may be tempting to use the S23 Ultra’s optical zoom lenses, you’ll have more flexibility by cropping into a 200MP shot as you can get the exact framing that suits you. Plus, framing your shot can be trickier than you think when you’re fully zoomed in using the optical zoom, as your hand’s minute and inevitable shakiness is magnified in addition to the subject you’re trying to shoot.

While there’s nothing stopping you from cropping into the S20’s 12MP shots, the details inevitably become fuzzier the more you crop in – from the legibility of the lettering to the brush and spray paint strokes – as you have far fewer megapixels to play with. Do bear in mind though that the S23 Ultra’s full 200MP mode works best when there is plenty of bright, even light.

Another caveat to remember is that 200MP images take up substantially more storage space than 12MP images – around 36MB compared to 3MB, respectively. So you’d need to ensure you have plenty of cloud storage space for backing up your shots, as well as fast upload speeds over Vodafone’s mobile and home broadband networks.

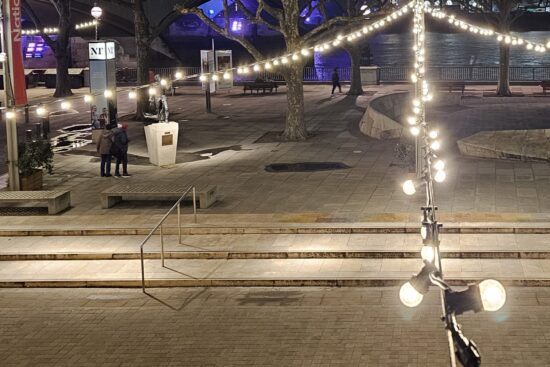

Landscapes in low light

This snap of London’s South Bank won’t win any photography awards, but this tricky scene does neatly illustrate the importance of dynamic range – accurately representing both the dark and light areas of a scene.

The S23 Ultra’s pixel-binned shot did a good job of capturing the brightness of the fairy lights, but without excessively over-brightening the shadow-soaked footpath beneath or losing any of the detail there to blurriness. The S20 not only struggled with the dynamic range of this admittedly tricky scene and in capturing the shadowy areas with acceptable levels of sharpness, it also needed far more attempts to capture a vaguely usable shot.

The S23 Ultra’s deft results are as much due to its software as to its camera hardware. Known as computational photography, this is where the traditional camera hardware in a phone – the imaging sensors and lenses – work in tandem with software to produce shots.

In this case, the camera app’s sophisticated algorithms recognised our scene full of light and dark areas, telling the camera to take multiple shots at different settings. It then took what it thought were the best bits from each shot, combining them together into a single shot, and then refining it further. Even more impressively, the entire process takes just a few seconds.

Computational photography occurs in almost every shot taken by a smartphone. This unassuming yet demanding South Bank scene is just one example of how sophisticated computational photography has become.

Portrait mode

Another example of computational photography is Portrait mode. This is when, in a shot of a person or pet, the background is discreetly blurred out so that the viewer’s focus is drawn subtly yet firmly onto the subject and not the background.

This background blurring, known as a shallow depth of field and as bokeh, is more difficult for smartphone cameras to achieve on-demand, compared to dedicated cameras, due to the size of their imaging sensors and physical construction of their lenses. Instead, to achieve the same effect, they often use software to tell the difference between the subject and the background in your shot and then apply a blurring effect to the background.

While the S20 made a valiant effort in this Portrait shot of our friendly neighbourhood cat, the bokeh effect has been overdone with heavily pronounced edges between the cat and the background. A blurring effect has also been mistakenly applied to the left eye.

While not a result of the 200MP sensor alone, the S23 Ultra’s effort was remarkably impressive. The smooth, gradual fade from subject to background looks naturalistic, for the most part. The only visible tell that this shallow depth of field is the result of software, rather than hardware alone, is the mild fritzing around the cat’s whiskers on the right hand side.

Shooting against the sun

To get the best results when shooting faces, it’s preferable to have your source of light (whether it’s the sun or artificial light such as a lamp) either behind you or shining from your left- or right-hand side onto the face of your subject. This not only avoids shrouding your subject in gloomy shade, it avoids a common problem when shooting outdoors – lens flare.

Sometimes though, you just can’t help yourself from snapping a scene even when the lighting isn’t in the best possible place. While it’s very difficult for any smartphone camera to minimise lens flare, as the S20 demonstrates, the S23 Ultra did remarkably well as our example shots show.

To get the Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra you want at a price you choose, head to the Vodafone website to learn more about flexible EVO pay monthly plans.

Stay up-to-date with the very latest news from Vodafone by following us on Twitter and signing up for News Centre website notifications.